Rewilding France met with Marine Drouilly to talk about the release of her book, Le Lynx boréal, published by Biotope.

⏱️15 minutes

Marine Drouilly is a passionate feline lover. She thrives on challenges. Wherever she goes, she ventures where no one else dares. In South Africa, where she currently lives, she deliberately avoids Kruger National Park, the country’s largest wildlife reserve, and instead chooses to visit the vast farms of the Karoo, where the challenges of coexistence with wildlife are truly critical. In the diverse environments where she works, from semi-arid deserts to rainforests, she sees animals in photographs, captured by her camera traps. If she ever sees them in real life, it’s only when she’s handling them to equip them with GPS collars. This contact with the wild is truly meaningful to her. The mere knowledge that she can walk in a rainforest still inhabited by giant pangolins, leopards, and golden cats thrills her. One day, while hiking along a steep mountain ridge in a mountainous area north of Cape Town, she has an unexpected encounter. She hears the call of a klipspringer, an African antelope, but the fog obscures her vision. Thinking her presence disturbs the animal, she moves away, but it continues to call. Marine retrieves the footage from the camera trap she had set up a few days earlier and returns home. It is only when she reviews the images on her computer that she understands the scene: one of the very rare Cape leopards had passed by just minutes before her. And the cry she heard was indeed the alarm of a klipspringer frightened by the large predator…

👉 Find the French version of the book Le Lynx boréal here

Rewilding France: Could you tell us a little about your background?

Marine Drouilly: I’m originally from Champagne in the Aube region, near Troyes. I studied in Paris and then worked all over the world for five years as a field biologist before starting a doctoral thesis on the interactions between livestock farmers and predators in South Africa. Then, in 2018, I joined the SFEPM (French Society for the Study and Protection of Mammals) to develop an action plan for the Eurasian lynx. In 2020, I was recruited by Panthera, an international organization working to conserve felines and their habitats worldwide, to work on the return of the leopard to Saudi Arabia, before turning my attention to the felines of Central and West Africa. I also voluntarily supervise the actions on the Eurasian lynx carried out by SFEPM employees.

RF: What led you to study the lynx?

MD: I met Patrice Raydelet* from the Pôle Grands Prédateurs while I was working on my thesis about conflicts between small livestock farmers and carnivores such as jackals, caracals, and leopards in South Africa. Patrice is passionate about all kinds of animals and, being from the Jura region, he’s passionate about the lynx too! He’s the one who introduced me to this animal… In fact, he’s the one who suggested my name to the SFEPM to draft the PNCL (National Plan for the Conservation of the Eurasian Lynx).

*Patrice Raydelet is an author, photographer, filmmaker, and lecturer committed to nature conservation, and also the founder of the Pôle Grands Prédateurs.

RF: Next step is a book…

MD: Yes, I was able to meet Jean-Yves Kernel, the Director of éditions Biotope, through a friend from Rewilding Europe, Fabien Quétier, who was working there at the time. The first PNA (National Action Plan) for the lynx is ending soon, in 2026, and this was therefore an opportunity to update our knowledge of the species, in preparation for the arrival of a second plan (Rewilding France’s note: the National Action Plan for the Eurasian lynx guides conservation efforts for this species and covers the period 2022-2026).

*Fabien Quétier is Coordinator with local teams for Rewilding Europe, he notably supervises our own territory, the Dauphiné Alps, covered by Rewilding France, and previously worked for Biotope as Research Director.

RF: Does your book propose an action plan for the lynx?

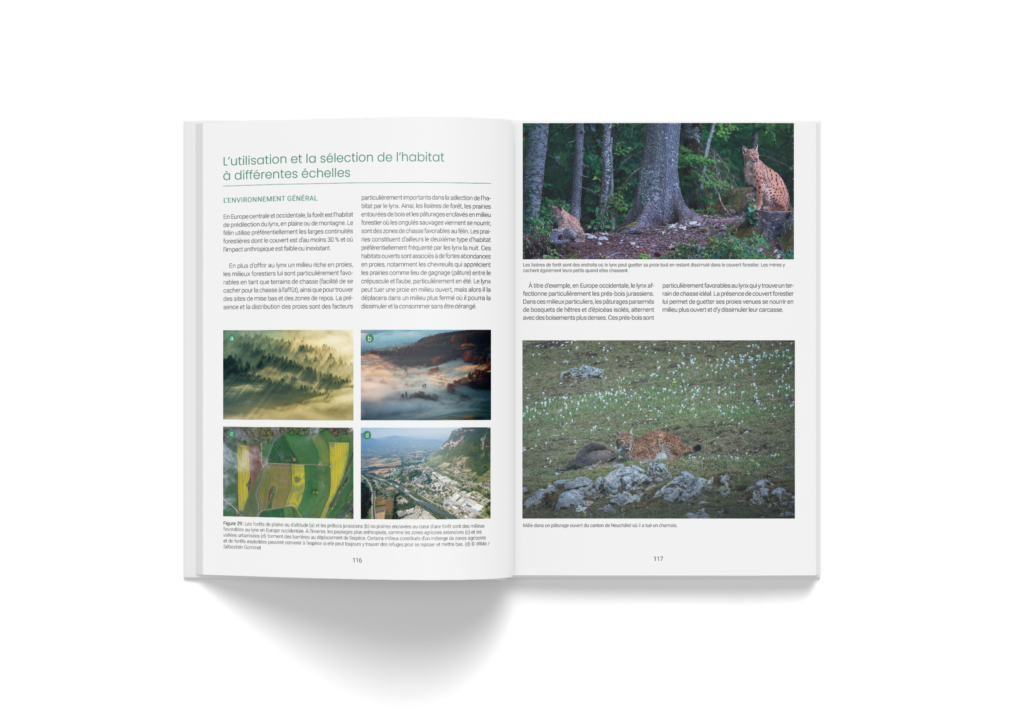

MD: The PNA is designed for that, not my book. The book is divided into three main parts: a large section on the lynx itself; a section on its ecology and biology, which notably discusses its interactions with the environment and other species; and a section on our relationship with the lynx. This last part is, for me, the most important in the current context.

RF: Why?

MD: We don’t have a single book in French that summarizes the reintroductions of the lynx across Europe and our relationship with this species from Prehistory to the present day. That’s the part I enjoyed writing the most. One of my scientific reviewers even told me, “Wow, you’ve written a bible on the lynx!” It might be a bit long, but it’s packed with information for anyone who’s passionate about the subject.

RF: How did you manage to write a book about an animal you’ve never seen?

MD: I reviewed all the scientific articles and reports that discussed the lynx, directly or indirectly, throughout its entire distribution range. I even translated articles into Russian! I spoke extensively with foreign experts on the species, not to mention the research conducted in France. I then had each section of my book reviewed and corrected by a scientific expert. The publisher and their team also did several proofreadings. The information was therefore meticulously verified. Even though I’ve never seen a lynx in the wild, as I don’t live in his habitat, I’ve already tracked one! I went into the field with Patrice Raydelet. We found tracks and, of course, faeces. We also collected samples for the SFEPM, which manages the collection of these samples, which are then analyzed to study the genetics of the species in France. I also accompanied several members of the PNCL, such as Jérôme Bailly and Christian Frégat, to check camera traps where lynx had been.

RF: What is it about the Eurasian lynx that attracts you so much?

MD: I’m very interested in carnivores in general. I find felines to be very beautiful animals, mysterious, and ultimately not so well understood. And then, they embody pretty much all the challenges we face in conservation today: they are strictly carnivorous animals with large home ranges whose habitats are increasingly fragmented; they come into contact with humans, which generates conflict; and they are culturally important, which makes them particularly vulnerable to illegal international trade.

RF: How do you explain the lynx is sometimes receiving negative press in France?

MD: People aren’t indifferent to felines: they either love them or hate them. And that’s what I like to study. Seeing all the emotions they generate in us and understanding how that translates into attitudes and behaviors. The lynx mainly hunts roe deer and chamois in France, and that’s why it’s sometimes viewed negatively by hunters who see it as a competitor.

RF: What exactly are we afraid of?

MD: Its predation on bushmeat for hunters and on livestock for farmers. In reality, there are few attacks: it’s 100 to 120 sheeps per year for the entire French lynx population. And this mainly concerns a few poorly protected farms, if ever protected, farms. There are some farmers who have small herds in isolated plots of land surrounded by forest, in the heart of the lynx habitat in the Jura Mountains. These herds can easily be attacked. A farmer who discovers his sheep killed by a lynx may experience severe psychological distress, anger, and helplessness, so it is a complex issue that should not be neglected, even if the number of sheeps killed is small.

RF: The lynx isn’t considered a problematic issue by the FNO (Rewilding France’s note: the National Ovine Federation), is that correct?

MD: The discussions I had with the FNO when I was writing the PNCL were perfectly reasonable, and I didn’t get the impression that they were fundamentally anti-lynx. The biggest challenge to be addressed in France today is with the hunters.

RF: When we look at the figures on the Eurasian lynx population, we see that there are 9,500 in Europe, but only about 200 individuals in France*… Is the lynx and France a troubled love story?

*Source: www.notre-environnement.gouv.fr, page on apex predators (last update on July, 6th, 2023)

MD: The Eurasian lynx doesn’t recognize our human boundaries; it doesn’t even stop at the borders of a continent. It inhabits a large part of Russia, China, Mongolia, Central Asia… It connects us to civilizations and landscapes that we barely know. When we look at each region of Europe and Asia where it is present, it is very often endangered, even though on a global scale, it is considered “Minor Concern” on the IUCN Red List (Rewilding France’s note: International Union for Conservation of Nature) due to its wide geographical distribution. Because it is present in so many places, people tend to think that everything is fine, but in Western Europe, the lynx is present in small, isolated populations with a very low number of founding individuals, so a general problem immediately arises: low genetic diversity.

RF: How can we genetically diversify populations that are isolated and have fragmented habitats?

MD: First, we need to work on restoring ecological corridors to allow lynx from these populations to move and meet. Secondly, once habitat connectivity is restored or underway, we can release lynx to introduce new genes, and even reintroduce the species into areas that connect populations. This can be done using lynx from captive breeding programs. The EAZA (European Association of Zoos and Aquaria) has genotyped all the lynx in European zoos and found that their genetic diversity is identical to that of wild lynx in the Carpathians. As a result: using individuals from zoos for these releases and reintroduction programs would prevent weakening the Carpathian population. Discussions are also taking place at the European level to use lynx that have been captured in the wild and cared for in rehabilitation centers, following accidents or illegal killing attempts, for example, to strengthen existing populations or create new ones.

RF: And why not directly releasing the lynx from zoos?

MD: We’d love to be able to do that, of course! But we also have to consider the animal’s ability to survive on its own once in the wild. A zoo lynx often becomes accustomed to the presence of humans and associates them with the food it receives without needing to hunt. This could create conflicts and an increased risk of illegal killing of these lynx. Poland recently released about a hundred individuals in Pomerania, all from zoos. Let’s just say it’s a different approach compared to Western Europe, where reintroductions are carried out on a smaller scale, generally around twenty individuals.

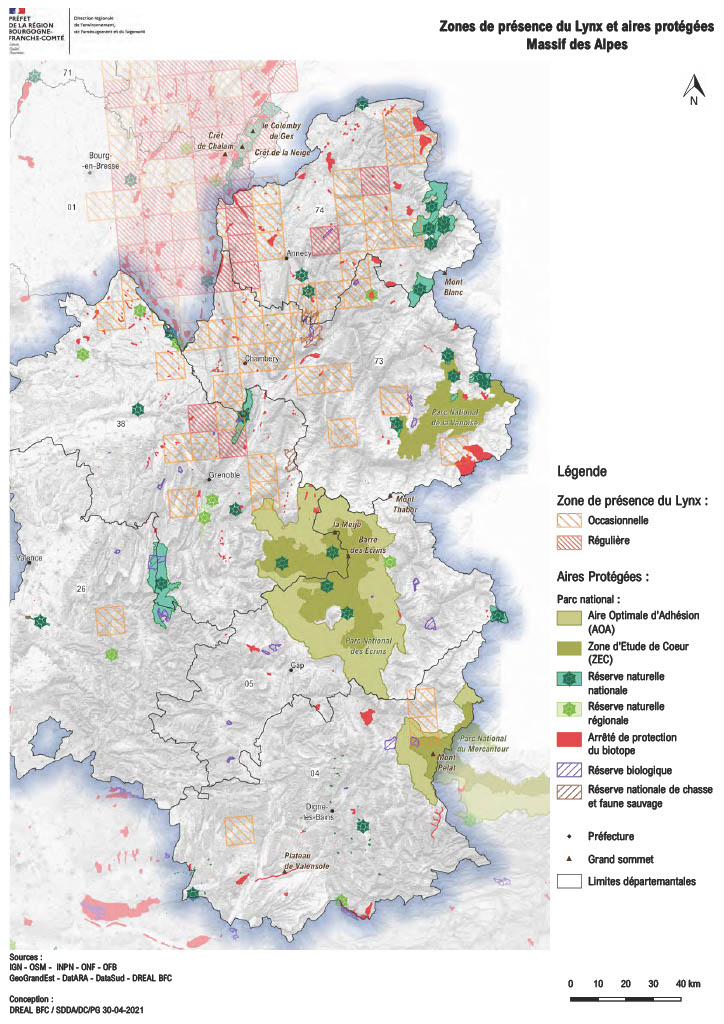

RF: Where can we find lynx in France?

MD: Mainly in the Jura, Ain, and Doubs departments. Lynx are being monitored in the southern Chartreuse mountains, and some individuals even pass through Grenoble, as lynx have been observed in the Écrins massif. We know there are some individuals in the Northern and Southern Alps, often dispersing males. They cover greater distances than females and are better at crossing obstacles. There are also colonization fronts, with some individuals in Saône-et-Loire and Haute-Marne, for example.

RF: Does this mean a presence in the Dauphiné Alps is possible in the long term?

MD: Currently, it’s mainly males that are colonizing these fronts, so it seems complicated without a helping hand and without improving connectivity between suitable habitats. As it has been done elsewhere, we would need to bring some females into the area to start building a real population. But before that, we would need to prepare people for a potential come back. Without social acceptance of the species, we risk failure and the illegal killing of released individuals.

👉 Click here to see this map in HD format

RF: Yes, because without this helping hand, the males have to backtrack during mating season to find females?

MD: Exactly, and they risk road collisions. Unfortunately, that’s how we sometimes know these males exist, because we find them injured on the road. That’s what happened in the Écrins mountains, and in Haute-Saône as well…

RF: Do you believe that the French political and social contexts are favorable to the lynx?

MD: What’s certain is that nothing can be done without the public authorities. The next PNA for 2027 must incorporate the results of the ESCO, the Collective Scientific Expertise conducted jointly by the National Museum of Natural History (MNHN) and the French Office for Biodiversity (OFB) in an interdisciplinary approach combining ecology and human and social sciences. Their recommendations are clear: improve ecological connectivity, reinforce/reintroduce lynx populations, and reduce illegal killings and collisions.

RF: We often picture lynx as solitary animals. Do they ever live in groups?

MD: Females have smaller territories than males, and these territories often overlap, but this depends on many factors. Adult male territories almost never overlap, whereas within a male’s territory, there may be territories of several females and subadults—males or females. The young become independent around ten months of age. They then leave their mother’s territory: this is called dispersal. Females often disperse “little by little,” finding a territory right next to their mother’s, while males go off to explore further. This is quite typical among large carnivores.

RF: So the lynx accepts communal living during mating season and the first few months of its cubs lives. Does it remain solitary the rest of the year?

MD: That’s a widespread belief, mainly due to a lack of scientific data on their social behavior. We’re seeing more and more encounters outside of these periods, for example, males visiting females until they give birth, sometimes even until the cubs are able to leave the den. APACEFS (Rewilding France’s note: Association for Alternative Protections for the Coexistence of Livestock and Wildlife) observed several individuals together in the Ain region, outside of the breeding season, perhaps to travel part of the way together (laughs). And we’ve seen this in other so-called “solitary” felines like the jaguar, so yes, they are mainly solitary, but there is still room for other social interactions!

RF: How do we manage to learn all of this about an animal that is so difficult to observe?

MD: Generally speaking, monitoring is done primarily using camera traps and VHF and GPS collars that are placed on the animals for a specific period of time (Rewilding France’s note: VHF stands for Very High Frequency, collars have the advantage of being cheaper and lighter than GPS collars, but are less precise, hence the need to use a combination of both types). These techniques are quite recent, which is why we are still discovering many behaviors that were previously unknown, even in species that we think we know well. And that’s what makes our job as field biologists so rewarding: there are always lots of new things to discover, lots of behaviors that we didn’t suspect at the start and that we’re going to be able to bring to light.

RF: Did you feel you were missing some data to be able to write this book?

MD: Yes, of course, there’s always missing data. And yet, the lynx is one of the best-studied felines. But you see, for example, there are only two or three studies in the world that discuss the interaction between wolves and lynxes. It’s very poorly documented. Many people assume there will be direct competition, where the two predators will hunt each other or one will gain the upper hand. But when you look at Africa, for example, where there are guilds with sometimes five, six, or even seven predators in the same habitat, you realize that there are mechanisms that the species put in place to allow their coexistence, for example, by using slightly different environments or at different times of day. The prey species consumed are also sometimes different. Wolves and lynxes don’t eat the same thing (Rewilding France’s note: wolves, hunting in packs, prefer to prey on deer and wild boar, while lynxes have a clear preference for roe deer and chamois). Their activity peaks differ slightly, although both can be nocturnal. I think they can certainly coexist, as in Russia or Northern Europe, even if occasional interactions and competition remain entirely possible…

RF: What can we wish for your book?

MD: That it becomes the French reference work on the lynx, that would be fantastic! I certainly hope to reach a wide audience, and especially to interest hunters, as there’s a lot of information in this book that directly concerns them. The project manager for the Jura Departmental Federation of Hunters (FDC 39) even wrote a sidebar in the book, as did many other experts. I hope this book will bring people together and that we can work together for the conservation of the lynx and for better coexistence with human activities.

Written by Aurélien Giraud

Rewilding France